The United States vs. Billie Holiday-Movie Review

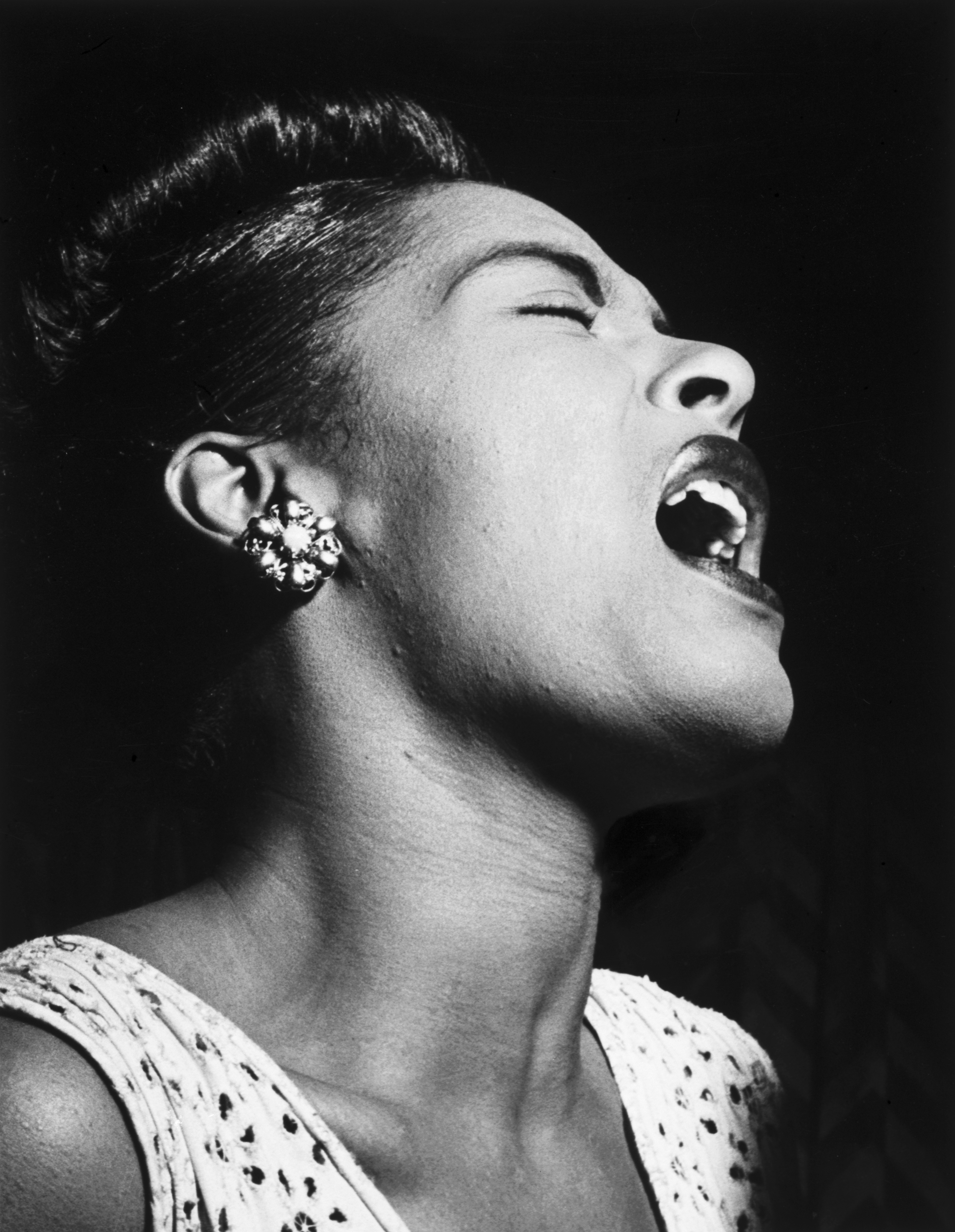

Andra Day brings Billie Holiday’s genius breathtakingly to life in a film that exposes the war on drugs as a “war on Black excellence.”

The United States vs. Billie Holiday, streaming on Hulu, is the latest truth-baring movie produced and directed by Lee Daniels. Speaking to the Guardian, Daniels acknowledged that the movie is “a call to arms, because we’re in dangerous times.”

Times that echo the U.S. government’s harassment of Holiday from about 1939 until her death in 1959. This is no simple protest movie. A chapter in Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream inspired the bold screenplay by Suzan-Lori Parks. Musically lush and visually stunning, the film stars Andra Day as Billie Holiday. Center stage is Holiday’s lonely, fiery courage as drug-addiction and government persecution burn through her relationships.

Why Billie Holiday?

The film’s conflict centers around the song, “Strange Fruit,” which Holiday first recorded in 1939. The song has been called “musical propaganda” and “a declaration of war.” The sardonic lyrics, written by Abel Meeropol, render in just 3 stanzas the brutal horror of lynching. But Holiday’s wrenching vocal styling combined with her intentional staging at live performances left her audiences unable to ignore the atrocities the song depicted. Emphasizing the lyrics with her improvisational tempo, her silken rasp and lilting vibrato manipulating syllables and layering intensity, Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” for eager audiences for 20 years. It was Holiday’s genius to break into our hearts with her voice, and Andra Day brings that genius breathtakingly to life.

Then and Now

The film is double-framed, opening with an image of a crowd of White men and boys surrounding a charred murder victim. The caption refers to the failed attempt to pass a 1937 anti-lynching bill (the film will close noting the as-yet unpassed Emmett Till Antilynching Act, received in the Senate in February of 2020 only to languish). The second half of the double frame is Holiday in a fictional 1957 interview with fabulously flippant Reginald Lord Devine (Leslie Jordan) asking why she keeps singing “Strange Fruit” when she gets in trouble for it. The question forces context, asked in McCarthy’s 1950s. Holiday’s film response rings of the 21st century: that the song is about human rights. The government wants her to shut up and sing any other song. The film’s opening makes clear that institutional racism demands individual response.

Then, it dives into three stories: of Billie Holiday vs. herself, of her vs. federal government, and of the fictional love story between Holiday and the federal agent, Jimmie Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes).

Billie vs. Billie

Of the stories this movie tells, the heroine’s conflict with herself deepens the film and keeps us riveted. Andra Day portrays the singer living her gift and her wreckage. There is no predictable plunge into the childhood traumas of rape and sex-trafficking, already told in Lady Sings the Blues. Instead, Daniels delivers one surrealistic montage of deep traumas, sufficient allusion to what lay beneath Holiday’s surface. With no flashbacks dragging on momentum, Day portrays Holiday’s intelligence even when she’s making terrible choices. We see her bold integrity, undaunted by the marginalization of Black women, as she rages in the face of Jim Crow exclusions and persists in singing a song that scares powerful people.

Andra Day embodies Holiday wrestling with her demons while society bombards her with restrictions for being Black, female, LGBTQ+. But, this movie lacks something in the portrayal of Holiday. Though she is a worthy heroine, we don’t get all of her. She is asked by antagonistic men why she keeps singing “that song,” but what gave her the fortitude to continue? Where is the personal charisma that is evident in Holiday’s voice? She is lonely, surrounded by people putting her on a pedestal or pressing their feet on her neck. We see little of the light she must have shown her closest companions, as she repeatedly dumps faithful friends.

Holiday took responsibility for her drug addiction. She also recognized the cruelty of criminalizing addiction.

“Imagine if the government chased sick people with diabetes, put a tax on insulin and drove it into the black market, told doctors they couldn’t treat them, then sent them to jail. If we did that, everyone would know we were crazy. Yet we do practically the same thing every day in the week to sick people hooked on drugs. The jails are full and the problem is getting worse every day.”

Billie Holiday, Lady Sings the Blues

Billie vs. Anslinger

The movie’s conflict between the government and Billie Holiday gains emotional impact from our investment in her personal struggle. Today, when governments of every level should finally reckon with and resolve institutional racism, the film spotlights how the government has long dehumanized people of color by inflating their association with drugs. In her interview with Oprah, Parks says she aimed to reveal the war on drugs as “a war on Black excellence.” The U.S. vs. Billie Holiday shows the beginning of this history, started under Harry Ansliger who served as the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. In the film, the efforts of Anslinger (James Hedlund) to prosecute Holiday for possession of heroin thinly conceal the goal of stopping her performance of “Strange Fruit.” Anslinger seethes at the threat to the WASP establishment, declaring “drugs and ni***rs are a contamination to our great American civilization.”

The real Anslinger?

There’s plenty in Anslinger’s real-life statements to back up the film’s portrayal of him as a racist. Anslinger conflated jazz with jungle music, racism turning his ear to tin. Hence, he’s an important antagonist, pulling the strings of several men in Holiday’s life who manipulated and exploited her. This element of the story suffers in impact since all the bad guys in Holiday’s life are flat characters. Still, as a representative of the federal government, Anslinger’s character reveals a system bent on maintaining power and oppressing people of color. These ruthless machinations have continued, through wars on drugs championed by Nixon, Reagan, Clinton, and Sessions/Trump, to misrepresent addiction as a Black-dominated crime.

“It was called ‘The United States of America versus Billie Holiday,’ and that’s just the way it felt.”

Billie Holiday, Lady Sings the Blues

Black American Patriotism

The segregated Black agents, in particular Jimmie Fletcher, embody the conflict between patriotic Black Americans and a government that rewards them with barriers and meager protections. Parks told The Hollywood Reporter “Black Americans love this country, often at our peril.” Through Fletcher, we witness Holiday’s patriotism compelling her to use her voice to protest; even Fletcher’s mother sees her as a hero for singing “for all of us.” Fletcher, an FBI agent who, the film emphasizes, comes from a successful family, believes that “drugs would be the death of [Black] people.” So, he gathers his evidence against her.

“Jimmy Fletcher is literally, actually an agent for the United States and she falls in love with him. To me, this is all about how we love this country and it dismisses us, and how for Black people, the fastest route to being an American is to throw someone of color under the bus.”

Suzan-Lori Parks told the Los Angeles Times

Scenes showing Holiday going through detox in prison are juxtaposed with those showing Fletcher hailed by Black agents as a road-paver for arresting her. While Holiday rose to fame from degradation, film-Fletcher’s family played by the rules and gained comfort and tenuous respectability. In the first half of the film, Fletcher blames Black criminals for bringing down all Blacks. By taking down Black criminals, he believes he’s making America better for Blacks who toe the line. The conflict takes a turn when Parks expands Holiday and Fletcher’s relationship into a love affair.

Fletcher: the ineffectual witness

There’s a strange flip in the story, here, when Fletcher’s attitude towards Holiday changes. In Holiday’s 2nd trial, Fletcher tries to stop Anslinger, testifying that someone may have set her up. Afterward, he tails her tour to protect her. He shoots up with her, as if it’s the only alternative to taking her down. This is his disappointing entrée into empathy for her. Without Fletcher’s help, Anslinger continues trying to imprison her, and she doesn’t stop singing her protest. So, the storyline of Fletcher representing the country Holiday loves fizzles rather than climaxing. He’s an ineffectual witness, but aren’t so many of us? While her spirit fights alone, parasites, poisons, and persecutors corrode her body until her death, under arrest in her hospital bed, in 1959.

At the end, the film is most honest. Billie Holiday died in shackles, without relenting to the government’s demands, without changing the racist system. Instead, she left a flicker of her flame in the spirits who respond to her song, reignited by this imprecise but important film.

Want to learn more about the truth behind the story?

-Billie Holiday worked with Louis Armstrong and Count Basie; however, her closest collab was with legendary saxophonist Lester Young (Tyler James Williams). She called him “Prez“, while he gave her the sobriquet “Lady Day.”

–Agent Harry Anslinger: “Marijuana: Assassin of Youth by Anslinger (Reader’s Digest version)

-Here, is the full audio of the the “Comeback Story interview portrayed in the film.

Have you seen the movie? What are your thoughts?

What can be done to resolve systemic racism?